Living Worlds

Previous dispatches of the (De-/Re-)Constructing Worlds project sought to probe the “what” of the project.

In addition to asking what makes a world in a general sense, the dispatches asked what specific kinds of worlds I envisioned making. In probing this “what”, the dispatches envisioned the makings of the following worlds:

Worlds in which the radicalism of everyday sense would counter both the populisms of common sense and the elitisms of higher senses and reasons;

Worlds in which working-for would be abolished in favor of working-with;

Worlds in which bioregionalisms, communisms, and dilettantisms would counter nationalist, capitalist, and careerist imperialisms;

Worlds in which humanisms would be overturned and primitivisms would be revalued;

Worlds in which the unity of life and its sufferings would be respected, even when that means sacrificing discipline.

Having probed the “what”, my next few dispatches will begin to probe the “how” — how will I go about making the worlds that I have envisioned?

A LIVING WORLD respects the unity of life and its sufferings, and it maintains and multiplies the wholeness of life.

A DEATHLY WORLD dismembers and dissects life and its sufferings, and it maintains and multiplies the parts that it plucks from life without respect for the wholeness of life.

The architect Christopher Alexander has proposed that the fundamental characteristic of a living world is that it is composed of “strong centers” or, to use an alternative term much more to my liking, Alexander has proposed that a living world is composed of STRONG FOCI. These strong foci are themselves, in turn, composed by and through processes that Alexander calls “structure preserving transformations”. Alexander finds fifteen of these processes in sum total, though he does not find that all fifteen of them are always needed to create a living world.

Being an architect, Alexander is primarily concerned with applying these “structure preserving transformations” to built environments in order to deconstruct deathly worlds and (re-)construct living worlds. Thinking through and beyond Alexander, I hold that the makings of meaningful statements and useful implements alongside built environments are, together, what constitute the makings of worlds. Consequently, I am interested in applying “structure preserving transformations” to meaningful statements and useful implements alongside built environments in order to deconstruct deathly worlds and (re-)construct living worlds.

The text below provides Alexander’s own definitions of the fifteen structure preserving transformations that he identified. In the bullet points below each of Alexander’s definitions, you will also find my own thoughts about the ways in which these processes apply not only to built environments but also to useful implements and to meaningful statements. Please note, however, that I have decided not to define what it means for a meaningful statement, a useful implement, or a built environment to have a “strong focus”. It is my wager that your own personal sense of what it means to have a “strong focus” will serve you far better than any definition I might provide here.

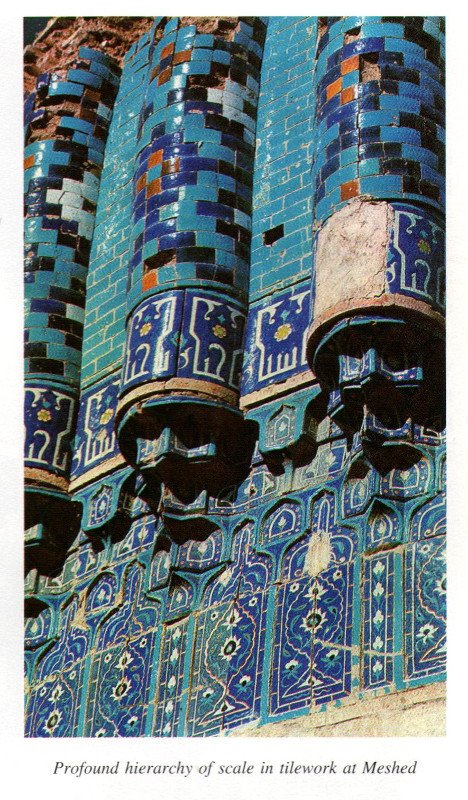

“… the small foci intensify the large ones … the large foci also intensify the small ones …”

LEVELS OF SCALE is “the way that a strong focus is made stronger partly by smaller foci contained in it, and partly by larger foci which contain it and relate it to other foci on its level.”

With respect to a given built environment — take an apartment building for instance — there are the several different “sub-environments” that are features of the given built environment — e.g., the hallways, stairwells, common use areas, parking garages, and the different apartments and their rooms. And then, of course, there are the “super-environments” or “encompassing landscapes” that count the given built environment as but one feature alongside others — the neighborhood that contains our apartment building, for instance, will have many other buildings in it and there will be built spaces between the many buildings in the neighborhood. Levels of scale are constructed (i) when the placements of the features of a given environment strengthen the focus of the given environment, and (ii) when the placements of the given environment relative to other environments in its encompassing landscape also strengthen the focus of the given environment.

With respect to a given useful implement — take a hammer, for instance — there are the different features that make up the given implement — e.g., the hammer’s handle, its neck, its face, its claw. And then there are the encompassing toolkits that count the given implement as but one feature amongst others — the toolkit containing the hammer, for instance, may also contain screwdrivers, pliers, a tape measure, etc. Levels of scale are constructed (i) when the uses of the features of the given implement strengthen the focus of the given implement, and (ii) when the uses of the given implement relative to those of other implements in its encompassing toolkit also strengthen the focus of the given implement.

With respect to a meaningful statement — let us take Foucault’s famous example of the “series of letters, A, Z, E, R, T, listed in a [French] typewriting manual” — there are the signifiers that are features of the given statement — e.g., “A”, “Z”, “E”, “R”, and “T”. And then there are the encompassing discourses that count the given statement as but one feature amongst others — a discourse around French typewriting might also contain a number of tables denoting of how prevalent accented letters and ligatures are in commonly written French words. Levels of scale are constructed (i) when the articulations of the features of the given statement strengthen the focus of the statement, and (ii) when the articulations of the given statement relative to other statements in its encompassing discourse also strengthen the focus of the given statement.

“The great courtyard, the large dome, the smaller dome, the individual battlements, the steps, the entrance, the individual arches, even the segments on the roof … the sequence of three domes, each one higher than the other, leading up to the main dome as a pinnacle. The entire structure builds up to the main dome …”

STRONG CENTERS (or, alternatively, ATTRACTORS) defines “the way that a strong focus requires a special field-like effect, created by other foci, as the primary source of its strength.”

“Strong centers” are constructed when a built environment that has a strong focus itself becomes the focus of a series of supporting environments in its encompassing landscape.

“Strong centers” are constructed when a useful implement that has a strong focus itself becomes the focus of a series of supporting implements in its encompassing toolkit.

“Strong centers” are constructed when a meaningful statement that has a strong focus itself becomes the focus of a series supporting statements in its encompassing discourse.

“The door as a focus is intensified by placing a beautiful frame of foci around that door. The smaller foci in the boundary are also intensified, reciprocally, by the larger focus which they surround ...”

BOUNDARIES (or, alternatively, HORIZONS) defines “the way in which the field-like effect of a focus is strengthened by the creation of a ring-like focus, made of supporting foci which surround and intensify the first. The boundary also unites the focus with the foci beyond it, thus strengthening it further.”

Again, a built environment that has a strong focus will become the focus of other supporting environments in its encompassing landscape. Boundaries are constructed when these supporting environments circumscribe the environment that is the primary focus. This is to say, in other words, that the placement of the primary environment come to be circumscribed by the placement of its supporting environments, and the placement of supporting environments also relates the primary environment to other environments that do not support it.

Again, a useful implement that has a strong focus will become the focus of other supporting implements in its encompassing toolkit. Boundaries are constructed when these supporting implements circumscribe the implement that is the primary focus. This is to say, in other words, that the uses of the primary implement come to be circumscribed by the uses of its supporting implements, and the uses of supporting implements also relates the primary implement to other implements that do not support it.

Again, a meaningful statement that has a strong focus will become the focus of other supporting statements in its encompassing discourse. Boundaries are constructed when these supporting statements circumscribe the statement that is the primary focus. This is to say, in other words, that the articulations of the primary statement come to be circumscribed by the articulations of its supporting statements, and the articulations of supporting statements also relate the primary statement to other statements that do not support it.

“… in Brunelleschi’s Foundling Hospital, the round medallions alternate within the columns and column bays. We see the columns repeating … the arches repeating … space of bays repeating … triangular space between adjacent arches repeating … ceramic roundels in these triangles repeating … Each of these things … is a profoundly formed and living focus. The result is beautifully harmonious and has life.”

ALTERNATING REPETITION is “the way in which foci are strengthened when they repeat, by the insertion of other foci between the repeating ones.”

Alternated repetition is constructed by repeated placements of one built feature in alternation with other such features of a given environment or encompassing landscape.

Alternated repetition is constructed by repeated uses of one useful feature in alternation with other such features of a given implement or encompassing toolkit.

Alternated repetition is constructed by repeated articulations of one meaningful feature in alternation with other such features of a given statement or encompassing discourse.

“In this plan each bit of every street is positive, the building masses are positive, the public interiors are positive. There is virtually no part of the whole which does not have definite and positive shape. This has come about, I think, because of how these spaces … have been shaped over time by people who cared about them, and they have therefore taken a definite, cared for shape with meaning and purpose …”

“In the present Western view … we tend to see buildings floating in empty space … the buildings … have their own definite physical shape — but the space which they are floating in is shapeless, making the buildings almost meaningless in their isolation. This has a devastating effect: it makes our social space itself — the glue and playground of our common public world — incoherent, almost non-existent …”

POSITIVE SPACE [AND TIME] is “the way that a given focus must draw its strength, in part, from the strength of other foci immediately adjacent to them.”

To create positive space [and time], a built feature must draw its strength of focus, in part, from the focus of other built features placed immediately beside them in space [and immediately before and after them in time].

To create positive space [and time], a useful feature must draw its strength of focus, in part, from the focus of other useful features that are put to use immediately beside them in space [and immediately before and after them in time].

To create positive space [and time], a meaningful feature must draw its strength of focus, in part, from the focus of other meaningful features articulated immediately beside them in space [and immediately before and after them in time].

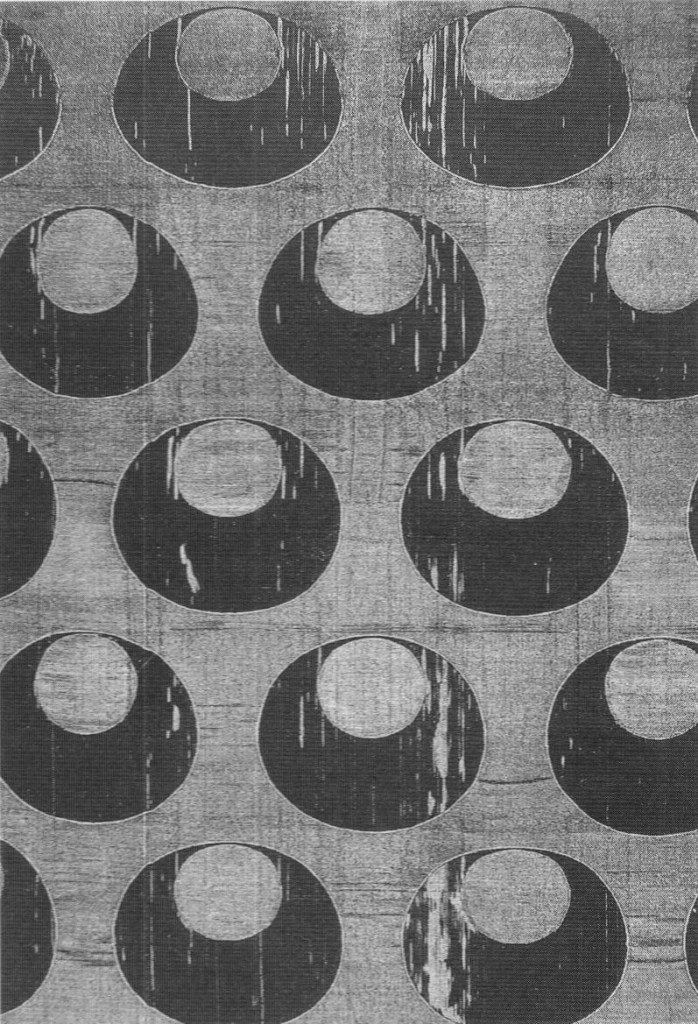

“The good form is an attribute of the whole configuration, not of the parts; but it comes about when the whole is made of parts that are themselves whole in this rather simple geometric sense …”

“… The high degree of sophistication needed to make a circle have good form is seen in the fabulous Ottoman velvet … where the two systems of circles are drawn slightly distorted so that the moon shapes, the space between the circles, and the small circles and large circles all work as foci.”

GOOD FORM is “the way that the strength of a given focus depends on its actual form, and the way this effect requires that even the form, its boundary, and the space and time around it are made up of strong foci.”

To create good form, every built feature of a given environment or encompassing landscape should contribute to the strength of focus of other such features of its given environment or encompassing landscape.

To create good form, every useful feature of a given implement or encompassing toolkit should contribute to the strength of focus of other such features of its given implement or toolkit.

Every meaningful feature of a given statement or encompassing discourse should contribute to the strength of focus of other such features of its given statement or encompassing discourse.

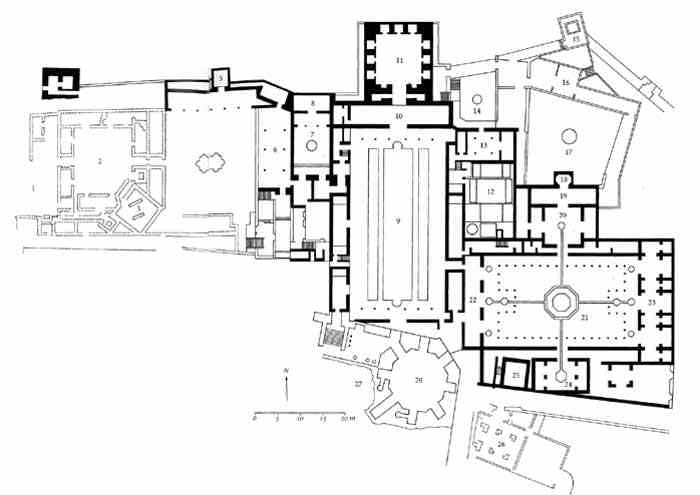

“We see this clearly in the Alhambra … a marvel of living wholeness. It has no overall symmetry at all, but an amazing number of minor symmetries, which hold within limited pieces of the design, leaving the whole to be organic, flexible, adapted to the site.”

LOCAL SYMMETRIES defines “the way that the intensity of a given focus is increased by the extent to which other smaller foci which it contains are themselves arranged in locally symmetrical groups.”

The built features of a given environment or encompassing landscape should be placed in such a way to create locally symmetries.

The useful features of a given implement or encompassing toolkit should be used in such a way to create locally symmetries.

The meaningful features of a given statement or encompassing discourse should be articulated in such a way to create locally symmetries.

“In a surprisingly large number of cases, living structures contain some form of interlock: situations where foci are ‘hooked’ into their surroundings. This has the effect of making it difficult to disentangle the focus from its surroundings.”

“… a similar unification is accomplished through the creation of spatial ambiguity … a common example … is the house with a gallery or arcade round it … the space in the gallery belongs to the outside world and yet simultaneously belongs to the building.”

DEEP INTERLOCK AND AMBIGUITY (or, alternatively, ENTANGLEMENT AND INDETERMINACY) is “the way in which the intensity of a given focus can be increased when it is attached to a nearby focus, through a third set of foci that ambiguously belong to both.”

Again, a built environment that has a strong focus will become the focus of other supporting environments in its encompassing landscape. These supporting environments should circumscribe the environment that is the primary focus. This is to say, in other words, that the placement of the primary environment ought to be circumscribed by the placement of its supporting environments, and the placement of supporting environments should also relate the primary environment to other environments that do not support it. Furthermore, these supporting environments should ambiguously belong to the primary environment and to the other non-supporting environments that they relate the primary environment to.

Again, a useful implement that has a strong focus will become the focus of other supporting implements in its encompassing toolkit. These supporting implements should circumscribe the implement that is the primary focus. This is to say, in other words, that the uses of the primary implement ought to be circumscribed by the uses of its supporting implements, and the uses of supporting implements should also relate the primary implement to other implements that do not support it. Furthermore, these supporting implements should ambiguously belong to the primary implement and to the other non-supporting implements that they relate the primary implement to.

Again, a meaningful statement that has a strong focus will become the focus of other supporting statements in its encompassing discourse. These supporting statements should circumscribe the statement that is the primary focus. This is to say, in other words, that the articulations of the primary statement ought to be circumscribed by the articulations of its supporting statements, and the articulations of supporting statements should also relate the primary statement to other statements that do not support it. Furthermore, these supporting statements should ambiguously belong to the primary statement and to the other non-supporting statements that they relates the primary statement to.

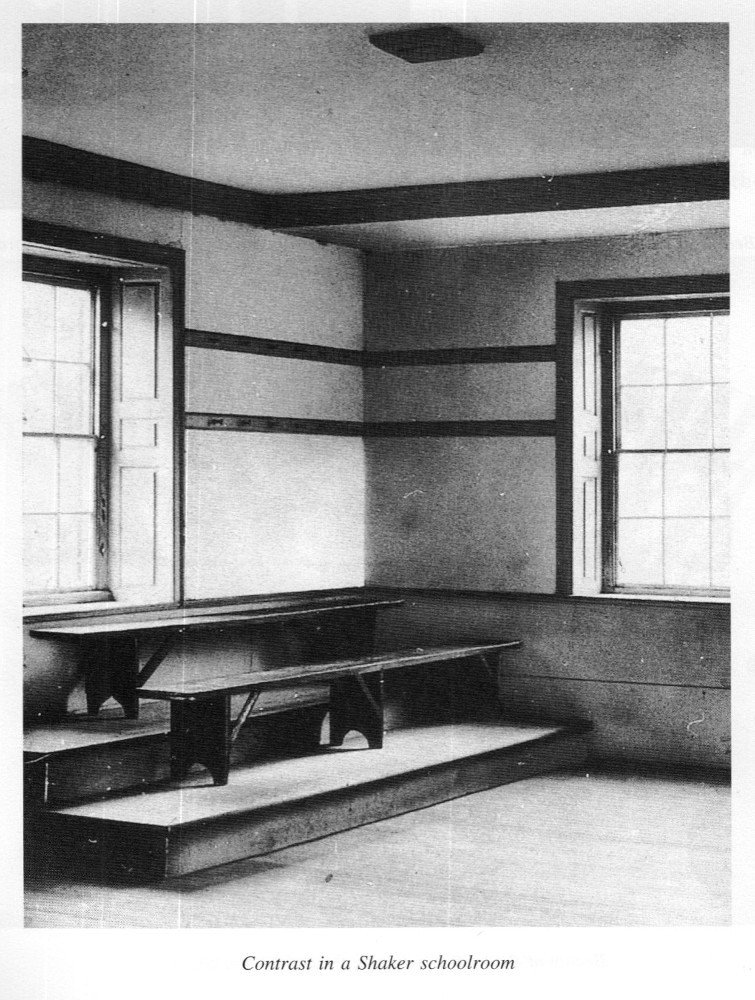

“In the case of the Shaker classroom … the two bands of wood above shoulder level, because of contrast, form a definite focus which would not be there or felt strongly — if the wood were pale … The focus which is so formed helps the room to become one, unified …”

CONTRAST is “the way that a foci is strengthened by the sharpness of the distinction between its character and the character of surrounding foci.”

The placements of the environment that is the primary focus should sharply contrast with the placements of the environments that support and circumscribe it.

The uses of the implement that is a primary focus should sharply contrast with the uses of the implements that support and circumscribe it.

The articulations of the statement that is a primary focus should sharply contrast with the articulations of statements that support and circumscribe it.

“… Gradients must arise in the world when the world is in harmony with itself simply because conditions vary. Qualities vary, so foci which are adapted to them respond by varying in size, spacing, intensity and character. Daylight varies from the top floor of an urban building to the bottom floor: both windows and ceiling heights will probably have to vary to adapt to these conditions …”

“… These gradients will also form foci because the field-like character which is needed to make every strong focus is precisely that oriented, changing condition which ‘points’ towards the focus of the focus …”

“Buildings and artifacts without gradients are more mechanical. They have less life to them, because there is no slow variation which reveals the inner wholeness …”

“… although gradients are commonplace in nature and in much traditional folk art, they are nearly non-existent in much of the modern environment. That is, I think, because the naive forms of standardization, mass production … and regulation of sizes … all work against the formation of gradients, and almost do not allow them to occur.”

GRADIENTS defines “the way in which a focus is strengthened by a graded series of foci which then "point" to the new foci and intensify its field effect.”

The placements of the environments that are of primary focus should involve the placement of graded series of built features whose placements strengthen the primary focus.

The uses of the implements that are of primary focus should involve the use of graded series of useful features whose uses strengthen the primary focus..

The articulations of the statements that are of primary focus should involve the articulation graded series of meaningful features whose articulations strengthen the primary focus.

“… The seemingly rough arrangement is more precise because it comes from a much more careful guarding of the essential foci in the design.”

“… Roughness can never be consciously or deliberately created. Then it is merely contrived. To make a thing live, its roughness must be the product of endlessness, the product of no will … Roughness is always the product of abandon — it is created whenever a person is truly free, and doing only what is essential.”

“… Roughness does not seek to superimpose an arbitrary order over a design, but instead lets the larger order be relaxed, modified according to the demands and constraints which happen locally in different parts of the design.”

ROUGHNESS (or, alternatively, NOISE) is “the way that the field effect of a given foci draws its strength, necessarily, from irregularities in the scales, forms and arrangements of other nearby foci.”

The environments that support and circumscribe a primary environment should have features that vary randomly in their placements.

The implements that support and circumscribe a primary implement should have features that vary randomly in their uses.

The statements that support and circumscribe a primary statement should have features that vary randomly in their articulations.

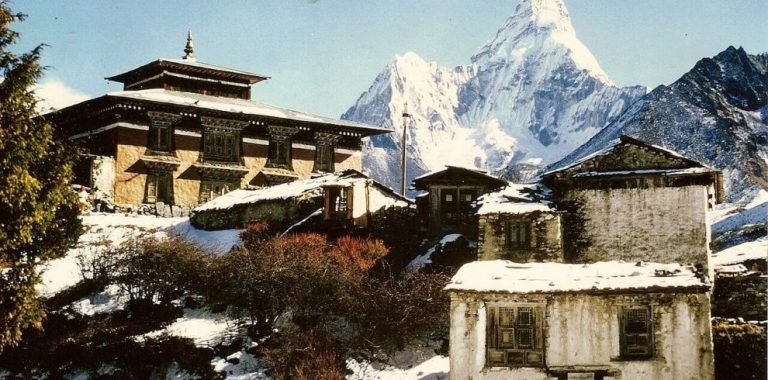

“… in the Himalayan monastery all the parts — stones, caps, doors, and steps — are heavily square with a line and a shallow angle … In Thyangboche, the monastery in the foothills of Everest, we feel in some profound and subtle way that this building is part of the mountains: part of the Himalayas themselves. The angles of the roofs, the way the small roof sits on the larger roof, the ‘peak’ on the largest roof, the band below the roof edge — all reflect or echo one another, and echo the structural feeling of the mountains themselves.”

ECHOES defines “the way that the strength of a given foci depends on similarities of inclination and orientation and systems of foci forming characteristic inclinations thus forming larger foci, among the foci it contains.”

Relations between a one primary environment and its supporting environments in a given landscape should echo the relations between other primary environments and their supporting environments in the given landscape.

Relations between a one primary implement and its supporting implements in a given toolkit should echo the relations between other primary implements and their supporting implements in the given toolkit.

Relations between on primary statement and its supporting statements in a given discourse should echo the relations between other primary statements and their supporting statements in the given discourse.

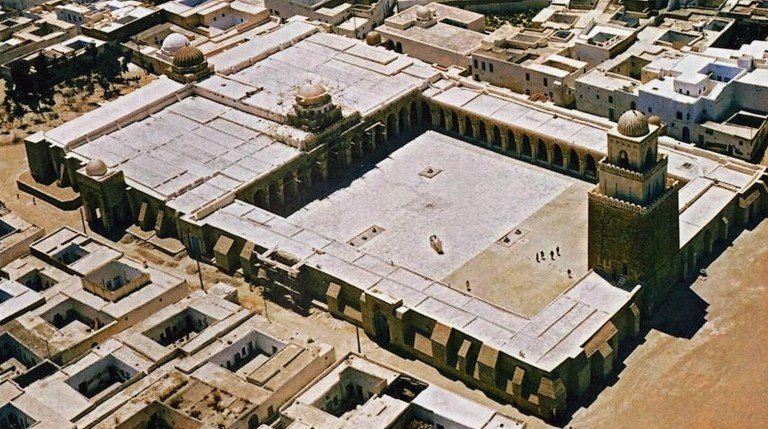

“In the most profound foci which have perfect wholeness, there is at the heart a void which is like water, infinite in depth, surrounded by and contrasted with the clutter of the stuff and fabric all around it …”

THE VOID is “the way that the intensity of every foci depends on the existence of a still place — an empty foci — somewhere in its field.”

Every built feature of a given environment or landscape should draw strength of focus from the unbuilt features that are a part of the given environment or landscape.

Every useful feature of a given implement or toolkit should draw strength of focus from the useless features of the given statement or discourse.

Every meaningful feature of a given statement or discourse should draw strength of focus from the meaningless features that are a part of the given statement or discourse.

“The quality comes about when everything unnecessary is removed. All foci that are not actively supporting other foci are stripped out, cut out, excised. What is left, when boiled away, is the structure in a state of inner calm. It is essential that the great beauty and intricacy of ornament go only just far enough to bring this calm into being, and not so far that it destroys it …”

“Simplicity and inner calm is not only to be produced by simplicity … the wild Norwegian dragon … has inner calm even though it is so complex … So it is not true that outward simplicity creates inner calm; it is only inner simplicity.”

SIMPLICITY AND INNER CALM is “the way the strength of a foci depends on its simplicity — on the process of reducing the number of different foci which exist in it, while increasing the strength of these foci to make them weigh more.“

Aim to reduce the number of built features belonging to an environment and its encompassing landscape while also strengthening the foci of the environment and its encompassing landscape.

Aim to reduce the number of useful features belonging to an implement and its encompassing toolkit while also strengthening the foci of the implement and its encompassing toolkit.

Aim to reduce the number of meaningful features belonging to a statement and its encompassing discourses while also strengthening the foci of the statement and its encompassing discourse.

“The correct connection to the world will only be made if you are conscious, willing, that the thing you make be indistinguishable from its surroundings, that, truly, you cannot tell where one ends and the next begins, and you do not even want to be able to do so.”

“The sophisticated version of this rule, which comes about when we apply the rule recursively to its own products … which ties the whole together inside itself, which never allows one part to be too proud, to stand out too sharp against the next, but assures that each part melts into its neighbors, just as the whole melts into its neighbors, too.”

NOT-SEPARATENESS (or, alternatively, CONNECTEDNESS) is “the way the life and strength of a focus depends on the extent to which that focus is merged smoothly — sometimes even indistinguishably — with the foci that form its surroundings.”

Each built feature of an environment or landscape should merge smoothly with the other built (and unbuilt) features in its vicinity.

Each useful feature of an implement or toolkit should merge smoothly with the other useful (and useless) features in its vicinity.

Each meaningful feature of a statement or discourse should merge smoothly with the other meaningful (and meaningless) features in its vicinity