The Racial Fracture

In preparation for the relaunch of the AGAPE Seminar & Studio in January 2025, I am publishing a series of dispatches revisiting the histories, theories, and proposals explored in our earlier gatherings. Each installment seeks to clarify and expand upon key concepts that emerged, offering a foundation for the conversations to come.

This dispatch analyzes the first of two defining fractures of Empire in our time: the racial fracture. This fracture delineates a global hierarchy of inferior and superior races, with anti-Blackness at its foundation. The dispatch examines how race, space, and time are mobilized to sustain this division, focusing on Blackness as the universal marker of abjection within the global racial order.

The next dispatch in this series will turn to the second fracture, the environmental fracture, which underscores the ecological dimensions of Empire’s hierarchies, linking exploitation of the earth to the racialized exploitation of its peoples. Together, these dispatches map the double fractures that sustain Empire, grounding our future discussions in their intertwined logics.

The Analytics of Raciality

Race, Space, and Time

Denise Ferreira da Silva’s incredible books, Toward a Global Idea of Race and Unpayable Debt, illuminate how the “analytics of raciality” operates through three deeply entangled dimensions: demography, geography, and history. These dimensions form a global framework for organizing human populations into racial hierarchies, assigning distinct identities to specific spaces and temporalities while linking them to narratives of development, civilization, and progress.

Coloniality constructs race as a system of psychosexual, sociocultural, and geopolitical inferiority and superiority, with Blackness occupying the abject position as a universal signifier of defectiveness. The analytics of raciality sustains this racial order by codifying techniques of domination through demographic classification, geographic partitioning, and historiographic sequencing. Together, these dimensions naturalize the subjugation of non-white populations and justify their perpetual administration and control.

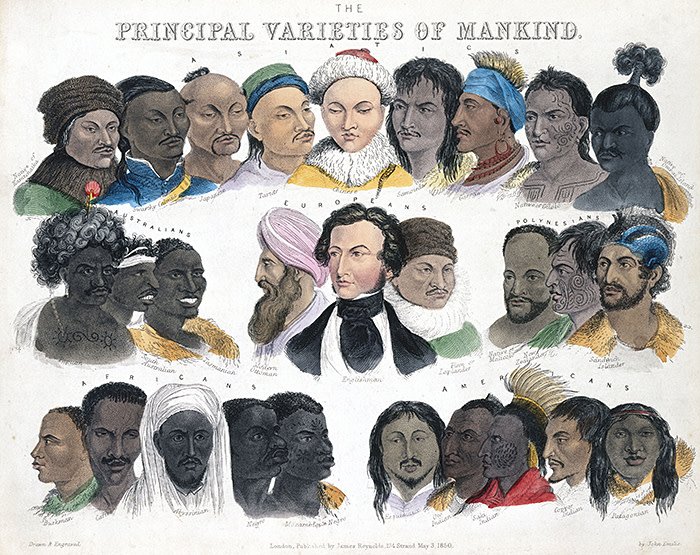

An 1850 engraving by John Emslie showing racial differences based on region of the world, grouped into six different headings. Today, many researchers continue to classify genetics by continental ancestry.

Demography: Determining Race

The dimension of demography in the analytics of raciality establishes racial categories—white, Black, red, brown, yellow—as seemingly universal and immutable markers of identity. These categories are far from neutral descriptors; they are constructs imbued with hierarchical value, positioning whiteness as the zenith or centerpiece of humanity and all other racial identities as lower or eccentric deviations. Blackness, in particular, is consistently cast as the most abject and deficient, associated with psychosexual, sociocultural, and geopolitical defects that are presumed to emanate from a subhuman biological essence.

This hierarchical racial taxonomy is central to the global colonial project. It informs the recognition, governance, and subjugation of populations within political, economic, and social systems. Blackness is constructed as the prototypical “problem” in these systems, embodying everything that whiteness is not: primitiveness, irrationality, criminality, and lack of progress.

The Myth of Racial Progress: The Race Relations Cycle

The liberal globalist myth of racial progress—articulated most explicitly by early 20th-century American sociologists through the “race relations cycle”—provides a framework for managing and ostensibly resolving racial differences. This cycle, described as “progressive and irreversible,” maps a trajectory from racial conflict to accommodation, assimilation, and ultimately amalgamation (miscegenation). It is a teleological narrative that assumes non-white groups must gradually abandon their “primitive” cultural traits, adopt the “civilized” culture of whiteness, and merge into the racial hierarchy through interracial unions.

However, as Denise Ferreira da Silva argues in Toward a Global Idea of Race, the race relations cycle is designed to fail when applied to Black populations. Blackness, unlike other racialized identities, is framed as an insurmountable barrier to full inclusion. Sociologist Robert E. Park, for instance, attributed this failure not to cultural differences but to physical traits, arguing that “the chief obstacle to the assimilation of the Negro” lay in the enduring visibility of Blackness. This visibility—encoded in phenotypic markers—renders Black bodies permanently estranged within the white-dominant world, regardless of their cultural or social adoption of whiteness.

The Role of Blackness in Racial Hierarchy

Blackness holds a unique and foundational position in the global racial order, functioning not merely as one among many racial identities but as the ultimate signifier of abjection against which all others are measured. Whiteness is constructed through its absolute opposition to Blackness, while other racialized groups are positioned along a spectrum based on their relative proximity to or distance from Blackness.

This dynamic entrenches anti-Blackness as a global phenomenon, enduring even in contexts where whiteness is no longer the dominant power. While non-Black groups may assert that they have equaled or surpassed whiteness, Black people and Blackness remain fixed as universal symbols of “the primitive,” “the slave,” and “the criminal.” These associations shape the governance and perception of all other racial identities. For example, even within liberal globalism’s multicultural narratives, Blackness is still denigrated, cast as a failure to assimilate, modernize, or adapt.

Racial hierarchies have occasionally conferred “honorary white” or “model minority” status on certain groups—such as the broad categorization of East Asians in apartheid South Africa or the specific designation of Japanese people as “honorary Aryans” in Nazi Germany. However, within these systems, Blackness and whiteness are constructed as immutable and opposing categories. Blackness, as a collective identity, is categorically excluded from “honorary white” and “model minority” status because the analytics of raciality position Blackness as the negation of whiteness—Blackness is equated with primitiveness, while whiteness is synonymous with civilization. While exceptional Black individuals from the so-called “talented tenth” may occasionally be granted a form of “honorary white” recognition, this distinction is framed as their personal transcendence of Blackness rather than as a redefinition or elevation of the Black race as a whole.

The persistent association of Blackness with “the primitive” legitimizes its perpetual management and control. Historically, enslavement was framed as the mechanism through which Blackness was introduced to “civilization,” serving as a model for subsequent systems of governance. This logic continues to operate today, manifesting in institutions like the prison-industrial complex, which treat Black populations as objects of control, experimentation, and administration

Demography as a Framework of Control

The analytics of demography extend beyond classification; they serve as a framework for governing and exploiting racialized populations. The hierarchies established through demography inform techniques of surveillance, labor extraction, and social control. Blackness is rendered a problem to be solved, whether through forced assimilation, containment, or elimination.

The logic of racial demography ensures that the racial hierarchy is reproduced across generations. Blackness is systematically excluded from the category of full humanity, framed as a defect that must be corrected through proximity to whiteness or erased through processes of miscegenation or eradication. Meanwhile, whiteness remains the unmarked standard, universal and invisible, against which all other identities are measured.

Geography: Spatializing Race

The second dimension of the analytics of raciality, geography, maps racial categories onto specific regions, producing a racialized cartography of the world. Whiteness is aligned with Europe and the West, Blackness with Sub-Saharan Africa, redness with the Americas, brownness with South Asia, and yellowness with East Asia. Transitional regions—such as Southeast Asia, Central Asia, West Asia, North Africa, and parts of Southern and Eastern Europe—are marked by hybrid categorizations. This spatial organization enforces a logic of racial difference that links identity to land, naturalizing racial distinctions as inherent, fixed, and immutable.

However, as Denise Ferreira da Silva’s work reveals, this spatialization is not monolithic; it adapts to regional histories and contexts, reflecting the flexibility of coloniality’s racial logic. The geographic codification of race takes on distinct forms in places like the United States and Brazil, demonstrating how racial hierarchies are shaped and reinforced differently based on local climates, economies, and colonial histories. While both regions perpetuate anti-Blackness and racial stratification, their mechanisms for doing so differ in ways that illuminate the broader operations of geography within the analytics of raciality.

The United States: Discrete Categories of Belonging

In the United States, racial geography is structured around rigid binaries that position Blackness and whiteness as fundamentally irreconcilable. Blackness is linked to enslavement, criminality, and subhumanity, while whiteness is idealized as the pure, unblemished standard of humanity. This binary sustains a racial hierarchy that obsessively polices the boundaries of whiteness, stigmatizing any perceived mixture with Blackness. The infamous “one-drop rule” institutionalized this ideology, perpetuating the notion that even the slightest trace of Black ancestry irrevocably marked a person as Black, making Blackness an inescapable and indelible identity.

By contrast, Native American ancestry is governed by the logic of blood quantum, which functions in the opposite direction. While one drop of Black ancestry permanently assigns an individual to Blackness, Native ancestry is imagined to dissolve into whiteness over generations through intermixture. Blood quantum thresholds for tribal belonging frame Native identity as something that diminishes with each successive generation, aligning with the settler-colonial goal of Indigenous erasure. Blackness, on the other hand, is constructed as an enduring stain that persists across generations, an unyielding mark of exclusion from whiteness.

These contrasting logics reveal the distinct mechanisms of racial domination in the settler-colonial project. Blackness is rigidly contained, perpetuated, stigmatized, and perversely fetishized as a threat to the purity of whiteness. Native identity, by contrast, is systematically eroded to fulfill the settler aim of eliminating Indigenous presence. Native blood is framed as a fleeting impurity that whiteness can absorb, while Black blood is treated as a contaminant that forever excludes individuals from the privileges of whiteness.

All other racialized groups are positioned in a precarious space between the Black and the Native, where proximity to whiteness confers a degree of social acceptability. It is more desirable to be seen as akin to the Native, who is imagined as assimilable, than to the Black, who is marked as perpetually outside the bounds of inclusion.

The spatial implications of this racial coding are profound. Whiteness is aligned with the temperate climates and perceived resemblance between North American and European landscapes, symbolizing spaces of civility, order, and governance. In contrast, Blackness, an import from the “uncivilizable” tropics, is relegated to spaces of captivity, exclusion, and labor exploitation. The spatial logic of the United States relies on rigidly fortifying divisions between spaces of whiteness and Blackness, upholding a vision of racial purity through systems of segregation and exclusion. This dynamic ensures that whiteness remains dominant and unchallenged, while Blackness is persistently marginalized, stigmatized, and confined to the periphery.

Brazil: Alloyed Whiteness in the Tropics

In Brazil, the geography of race operates through a different lens, emphasizing the logic of miscegenation and fluid gradations of racial identity rather than the rigid binary categories prevalent in the United States. As Denise Ferreira da Silva observes, Brazilian racism is anchored in the concept of “alloyed” whiteness, where whiteness derives strength and value through the calculated admixture of non-white ancestry. Unlike the American fixation on racial purity, Brazilian whiteness is constructed as adaptable and resilient, strategically fortified by miscegenation to endure the perceived challenges of the tropical environment.

This framework treats miscegenation not as a threat but as a mechanism for incorporating and ultimately erasing Blackness within a hierarchical racial order. Blackness is framed as an excess or defect to be gradually diminished through intergenerational mixing, producing “alloyed” whites deemed better suited to Brazil’s climate. The celebrated “career” of Africans in Brazil, as Silva describes, is defined not by empowerment but by disappearance—a process through which phenotypic markers of Blackness are systematically erased over generations, ensuring whiteness’s dominance while rendering Blackness increasingly invisible.

In Brazil, pure whiteness is not the ultimate ideal but rather a tempered and fortified whiteness. Blackness, however, is stigmatized as the most volatile and disruptive element to combine with whiteness, capable of producing profound psychosexual, sociocultural, and geopolitical “defects,” even in small amounts. Despite this, Blackness is paradoxically viewed as a useful element to alloy with whiteness when handled in controlled and minimal doses. Other racialized groups are considered less volatile and easier to assimilate, with Indigenous Brazilians occupying the opposite end of the spectrum from Black Africans. Much like in the United States, where Indigenous identity is constructed as less threatening and more assimilable, Indigenous Brazilians are seen as the least disruptive element, facilitating the production of an “acceptable” alloyed whiteness within the Brazilian racial hierarchy.

Geography and the Global Logic of Racialization

Both the United States and Brazil exemplify how geography is used to naturalize racial hierarchies, but their differing approaches are part and parcel of a broader, orverarching global logic. As Silva notes, the degree to which whiteness is valued in its “pure” or “alloyed” form depends on geography and climate. In temperate regions purported to resemble Europe, like North America, purity is privileged; in tropical regions purported to be hostile to European ways of life, like Brazil, admixture becomes a strategy for sustaining dominance.

This adaptability allows the analytics of raciality to maintain the underlying racial hierarchy across diverse contexts. Whether enforced through rigid segregation or subtle gradation, the spatial logic of coloniality ensures whiteness remains central and dominant, while Blackness is persistently marginalized and denigrated. Regions deemed entirely unsuitable for European settlement, such as parts of Central Africa, are often constructed as spaces of “primitive” subcultures. These spaces, perceived as suffering from the absence of whiteness, are still portrayed as imitating and distorting whiteness from a distance—“aping” and “corrupting” white ideals in a manner that reinforces the view of Blackness as the antithesis of modernity, civilization, and progress.

The Geography of Anti-Blackness

Anti-Blackness, as Silva argues, is a persistent and defining feature of this racial geography, shaping how spaces are valued, governed, and utilized. In both Brazil and the United States, Blackness is relegated to spaces of exploitation and containment, such as the plantation, the American ghetto, the Brazilian favela, or the prison. These spaces are critical to the operations of coloniality, functioning as laboratories for developing and refining techniques of control, extraction, and subjugation.

The global map of racialized spaces underscores the deeply interconnected dimensions of geography and demography. Blackness is consistently associated with Africa and the “primitive,” while whiteness is linked to Europe and the “civilized.” European expatriate enclaves, irrespective of their location, are constructed as symbols of order and progress, while Black neighborhoods outside Africa—whether in Europe, the Americas, or elsewhere—are stigmatized as sites of danger, degradation, and disorder. Globally, landscapes deemed desirable for settlement are marketed to European audiences as spaces of opportunity and prosperity, while poor Black African migrants are corralled into regions considered hazardous or toxic, reinforcing their exclusion from spaces of privilege and their confinement to zones of exploitation.

This spatialization does more than delineate where racialized bodies are permitted to exist; it naturalizes the unequal distribution of opportunity and resources. It legitimizes the expropriation of land and labor, framing such acts as necessary for progress. Colonial and postcolonial enterprises consistently portray themselves as benevolent missions to civilize or improve territories and populations deemed backward, unproductive, or threatening. Geography, in this context, serves as a mechanism for justifying domination: desirable spaces are reserved for whiteness and those proximal to it, while undesirable spaces are relegated to containment, marginalization, and extraction, particularly for Blackness and those furthest from whiteness. This dynamic not only sustains racial hierarchies but embeds them into the very landscapes and infrastructures that define the modern world.

Global Apartheid and the International Racial Hierarchy

Expanding this logic to global geopolitics, the international apartheid regime, solidified under United States hegemony, uses nationality as a proxy for race, reproducing the racial hierarchies entrenched within the hegemonic nation’s borders. Indigenous peoples without recognized nation-states are excluded entirely from this global racial order, rendered invisible and expendable within the frameworks of the global economy. Nations predominantly inhabited by those categorized as belonging to the “Negro” race—such as Black Africans and the most impoverished Caribbean populations, with Haiti serving as a stark example—are positioned at the very bottom, perpetually framed as zones of racial and economic deficiency.

Above the nations of Black Africa and the Caribbean in this global racial hierarchy are the so-called “coolie” nations of Asia, particularly India and China, whose populations were racialized during the era of slave emancipation as a labor force considered more “dependable” than free Africans. Competing alongside Asians are the settler-colonial nations of Latin America, whose populations, largely composed of “alloyed whites” and visibly mixed-race groups such as mestizos, pardos, and mulattos, are disparaged by white Europeans and North Americans for their supposed “racial impurities” and “deficient racial hygiene.”

Meanwhile, Eastern Europe, Western Asia, Southern Europe, and Northern Africa are cast as liminal zones, transitional spaces between the white European race and the racialized populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and South and East Asia. These regions occupy an ambiguous place within the hierarchy, simultaneously othered and partially assimilated into whiteness, their populations framed as intermediaries between the fully included and the fully excluded.

This global racial hierarchy marginalizes Black nations to the furthest periphery, systematically excluding them from meaningful roles in shaping the international order. It justifies interventions into the lives and lands of non-white populations under the guise of “civilizing missions,” often reframed as peacekeeping operations, development programs, or humanitarian aid. These narratives not only reinforce racial hierarchies but also embed them deeply within the international institutions that define the modern global system.

Geography and the Analytics of Raciality

The geographic dimension of coloniality does more than assign races to specific regions; it produces and sustains racial hierarchies by framing certain spaces as inherently superior or inferior. Africa is imagined as a land of ungovernable Blackness, perpetually in need of external administration. Europe, by contrast, is positioned as the seat of rationality and governance, radiating progress outward to the rest of the world.

This spatial logic reinforces the other dimensions of coloniality—demography and history—creating a comprehensive system for organizing human populations into hierarchical orders. The entanglement of geography with racial identity ensures that racial hierarchies are inscribed into the land itself, perpetuating systems of domination long after formal colonial rule has ended. As Silva’s work demonstrates, geography is not simply the backdrop for racial hierarchies; it is an active participant in their construction and perpetuation.

A plate from Charles White's "An Account of the Regular Gradation in Man and in Different Animals and Vegetables; and from the Former to the Latter," 1799.

History: Temporalizing Race

The historical dimension of coloniality weaves together the analytics of race and space by embedding temporal hierarchies into racialized identities. This framework constructs a linear timeline of progress that positions whiteness as the spearhead of modernity while relegating Blackness to the perpetual margins of primitiveness. Africa, central to this logic, is simultaneously cast as the origin of humanity and excluded from the trajectory of civilization, framed as stagnant and pre-modern.

Africa as the “Primitive” Origin

Africa holds a foundational role in the temporal logic of coloniality, positioned as the “dark continent,” frozen in time and outside the trajectory of historical progress until colonization ostensibly “rescued” it by introducing it to history. Framed as the epitome of primitive life, Africa is depicted as perpetually awaiting salvation through external intervention. This narrative has long been employed to justify colonial conquest, enslavement, and resource extraction, rebranded in contemporary times as peacekeeping, humanitarian aid, and development. Such interventions are far from altruistic; they function as mechanisms to sustain Africa as a space of social death, perpetually subjected to external control and oversight.

International institutions extend the dynamics of domestic anti-Blackness onto the global stage. Across Africa, peacekeeping forces and philanthropic organizations wield unchecked authority, echoing the impunity with which police and civil administrations operate in Black communities across the United States. Africa, the most heavily patrolled region by peacekeeping forces, is subjected to this militarized paternalism under the guise of humanitarianism. Both systems collaborate to sustain Africa’s depiction as a site of primitive failure, rationalizing its ongoing subjugation through the rhetoric of progress and benevolence.

By contrast, Asia is often depicted as home to age-old civilizations whose “genius” transferred westward to feed Western European modernity. China, India, and the Muslim world are acknowledged for their historical contributions but are framed as having stagnated at a crucial juncture, allowing the West to cross the finish line first and become the embodiment of universal progress. Africa, by contrast, is denied even this recognition of historical depth, reduced instead to a timeless void awaiting salvation.

This dual narrative reflects coloniality’s strategy of erasure and appropriation. Africa is exploited as a raw resource materially and symbolically, while Asia’s cultural and intellectual heritage is co-opted to affirm Western dominance. These narratives are not inherent truths but imposed constructions designed to justify global hierarchies.

Contrasting Temporalities: The Race Relations Cycle

The race relations cycle, a liberal globalist framework for racial progress, underscores the temporal dimension of coloniality. It imagines a progression from conflict to accommodation, assimilation, and finally amalgamation (miscegenation). While ostensibly universal, the cycle systematically excludes Black populations, particularly in Africa and its diaspora. In the United States, Blackness is marked by rigid binaries, with the infamous “one-drop rule” ensuring permanent exclusion from whiteness. Africa, in this schema, is the ultimate repository of failure, reinforcing Blackness as incompatible with progress.

In Brazil, the cycle adopts a different temporality. Blackness is not rigidly excluded but diluted through miscegenation, imagined as a process of whitening over generations. This logic treats Blackness as a defect to be erased, aligning with Brazil’s narrative of racial democracy while maintaining white dominance. Despite these regional differences, both frameworks converge in their treatment of Africa as a site of stagnation, justifying ongoing interventions that perpetuate the continent’s dependency.

Temporal Logic of Enslavement and Control

Enslavement exemplifies the historical mechanism through which Blackness is introduced to “civilization.” This logic persists in contemporary institutions such as the prison-industrial complex, development projects, and international border regimes. Africa is framed as the prototype of failure, perpetually requiring external governance. Its nations, many labeled “failed” or “fragile,” are treated as wards of an international order, Empire, that positions itself as the arbiter of civilization.

This framing extends to Black diasporic populations, who are subjected to the same logics of control. Migrants from Africa, fleeing poverty and instability, are profiled as “illegal immigrants” in wealthier nations, confined to zones of exploitation and subjected to heightened surveillance. These border regimes, as Silva argues, use nationality as a proxy for race, ensuring that Blackness is criminalized and excluded from full participation in global mobility and modernity.

Africa and Global Apartheid

The global racial order enforces a form of apartheid that marginalizes Africa and its diasporic populations. Militarized border regimes and bureaucratic immigration systems function as modern-day “pass laws,” preserving the privileges of wealthier, whiter nations while restricting the movement of migrants from the Darker Nations. Africa’s citizens endure the harshest restrictions, their exclusion reinforcing the continent’s role as a supplier of resources and labor rather than a participant in “progress”.

Black Africans who gain limited access to the wealthier core nations of Empire are often funneled into low-wage labor markets or forced to undervalue their labor despite possessing extensive credentials for higher-wage sectors. In these spaces, their contributions are systematically exploited while their humanity is devalued. This dynamic reflects Africa’s broader positioning within the global order as a site of extraction and control, where its worth is measured solely by its utility in sustaining the prosperity of others.

Black Quantum Futurism

From Ordered World to Entangled World

Denise Ferreira da Silva’s work compels us to confront and dismantle the “Ordered World” — the colonial world sustained by the analytics of raciality. This world naturalizes demographic determinability, geographic separability, and historiographic sequentiality, embedding and entrenching racial hierarchies in the techniques, infrastructures, and logics of policing, bordering, and governance. At its core, this order systematically excludes Blackness and all those proximal to it from full humanity, perpetuating domination and exploitation under the guise of progress and civility.

Silva challenges us not only to abolish the techniques of this order but also to deconstruct the epistemologies and ontologies that sustain it. She exposes how fixed identities, bounded spaces, and linear narratives of development legitimize systems of control and violence. By deconstructing the Ordered World, Silva envisions the possibility of an “Entangled World” — one characterized by demographic indeterminacy, geographic non-locality, and historiographic non-eventuality, which collectively foster an ethic of mutuality, care, and relationality.

Demographic Indeterminacy: This condition rejects rigid, hierarchical racial, ethnic, and cultural classifications. Demographic indeterminacy counters the colonial logic that uses fixed categories to dictate value, inclusion, and governance. Instead, it embraces the opacity, multiplicity, and confluence of identities, unmooring populations from rigid markers of difference that have historically justified domination.

Geographic Non-Locality: Geographic non-locality disrupts the colonial spatial logic that ties identity to bounded, segmented territories. It rejects the idea that certain people inherently “belong” to specific places, challenging systems of inclusion, exclusion, and dispossession. In the Entangled World, space is reimagined as relational, porous, and entangled, resisting the territorial fixity that reinforces control and exclusion.

Historiographic Non-Eventuality: This departure from linear, teleological history challenges the notion of universal developmental stages that all peoples are expected to progress through. Historiographic non-eventuality opposes the colonial narrative of “progress,” proposing instead a revolutionary, relational, non-causal and non-hierarchical understanding of time. It allows diverse temporalities to coexist, to influence one another, and to merge into confluences, refusing subordination to a single, Eurocentric timeline of advancement.

In the Entangled World, race no longer determines value or belonging, space is no longer carved into zones of inclusion and exclusion, and history no longer serves as a measure of developmental “success.” Silva’s vision challenges us to construct new techniques, technologies, and infrastructures of living that enable beings, places, and temporalities to co-exist and resist the colonial impulse to impose order and control.