A Black Planet

During my adolescence, one of the records that deeply shaped my thinking was Fear of a Black Planet by Public Enemy. The music captivated me, but the title lingered in my mind even more powerfully. I felt it encapsulated something fundamental about Empire—a fear not merely of a people but of a world transformed by Blackness. Years later, this idea resurfaced when I encountered members of the research collective Black Planetary Futures. The name of their collective, echoing the title of the Public Enemy record, compelled me to reflect once again on what it might mean to embrace or cultivate a Black planet.

This essay redefines Blackness as a condition that both exceeds and honors ancestry. While deeply rooted in shared African descent, Blackness also extends to those whose kinship is analogical and ecological. Black political formations, therefore, are not solely composed of people of African descent but also include those who, under comparable pressures, develop convergent or co-evolving strategies of resistance to racial capitalism’s violence. Analogical kinship arises from parallel adaptations to oppression, while ecological kinship emerges through interdependent struggles for survival and dignity. Yet, these kinships—particularly the analogical—have limits, as Black suffering remains singular in its gratuitousness. Unlike other forms of oppression, which are often rationalized within the system to serve a distinct function, Black suffering is senseless, without distinction, inflicted solely to heighten others’ sense of the distinctiveness of their own human suffering. This inquiry interrogates the boundaries of solidarity, the mythologies of labor exploitation, and the ritualized violence that sustains global civil society. Ultimately, it argues that ecological extensions of Blackness, rooted in mutual care and regeneration, offer the most viable pathway for enduring solidarities toward the planetary abolition of Empire, war, and accumulation by dispossession, degradation, and devastation.

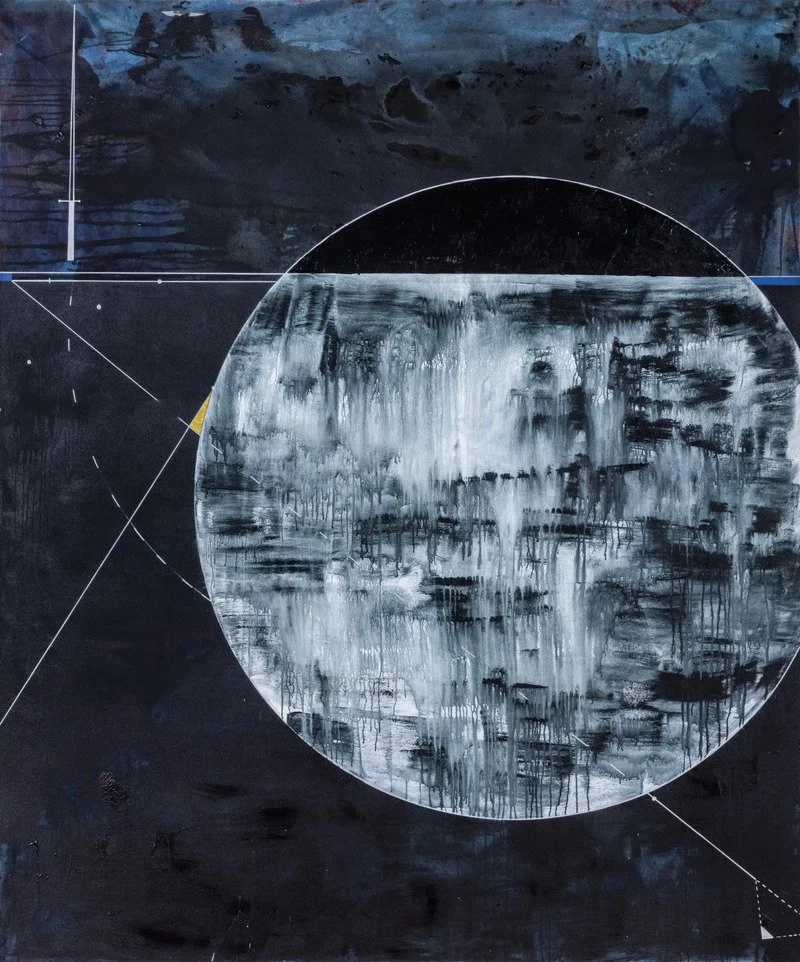

Torkwase Dyson, A Place Called Dark Black (Bird and Lava), 2020

Ecological Kinship and the Limits of Analogy

Homological kinship reflects shared ancestral origins, diverging over time due to differing environmental conditions and evolutionary trajectories. For instance, the bones within a whale’s fins and a bat’s wings—though specialized for vastly different functions—retain a common structural heritage. Life thus carries the memory of its beginnings through homology, adapting across epochs while preserving echoes of deep evolutionary inheritance. This shared foundation of ancestry informs how certain solidarities in Black political formations are built upon historical and genealogical ties.

Analogical kinship, however, does not arise from shared descent but from convergent adaptations. Organisms with no direct common ancestry can develop parallel traits in response to similar environmental pressures. For example, the elongated, limbless form of snakes has evolved independently across multiple reptilian lineages, offering analogous solutions to locomotion and predation. Similarly, some non-Black groups subjected to racial capitalism develop adaptations to oppression that mirror those of Black communities. Yet these analogies, as the essay will explore, often fall short due to the singular nature of Black suffering.

Ecological kinship, by contrast, is shaped through co-evolution and symbiotic interaction. Species evolve in mutual relationship, adapting to one another within interconnected ecosystems. The orchid Ophrys apifera exemplifies this dynamic, mimicking the pheromones of female bees to lure male bees as pollinators. Similarly, the elongated beaks of hummingbirds co-adapt with the tubular forms of flowers they pollinate. This deep interdependence highlights how life forms—neither homologous nor analogous—become mutually entangled through co-adaptive processes. In political terms, ecological kinship manifests in solidarities forged through the co-evolution of struggles, where the survival of one community is inextricably linked to the survival of another.

As noted, these categories—homological, analogical, and ecological—are not confined to biological systems but also illuminate the relational dynamics of Black political solidarities. While homological kinship reflects ties rooted in shared African ancestry, Black political formations, like the Rainbow Coalition formed by the Black Panthers, also incorporate analogical and ecological relationships. Analogically, groups with no direct Black ancestry in the context of modernity—such as Aboriginal Australians—have developed parallel adaptations to racial oppression, drawing inspiration from Pan-African movements and aligning with Black liberation struggles. Ecologically, Native American communities have co-evolved resistances alongside Black movements, their intertwined histories of dispossession and resilience fostering solidarities across generations. These multifaceted kinships illustrate how Black political formations resist the fragmenting logics of racial capitalism through both deep ancestry and adaptive interdependence.

Blackness, then, encompasses all who share a homological, analogical, or ecological relationship to the “Negro” experience. As articulated by R.A. Judy in Sentient Flesh, this experience is shaped by the violent interpolation of peoples and cosmogonies into capitalism’s global order:

“[I]nterpolation into capitalism’s terms of order […] results in the dissolution of long-enduring formations of human community, engendering cosmic disorder by throwing disparate cosmogonies together under the anthropological rubric primitive. This term has a rather broad connotation, comprehending both an original inhabitant, an aboriginal, and a person belonging to a preliterate nonindustrial society, but also ancestral early man, or anything else that is archaic. It has been inclusively applied to a wide array of types of natives—also a conceptual category—engendered along the way in capitalism’s global expansion and colonial rule. Not all colonial natives are designated primitive, however; there are those who belong to age-old civilizations, the effects of which, according to the narrative of translatio, transferred westward to feed the foundations of capitalism—outstanding examples of which are China, India, and most of the Muslim world. The distinction of having been civilizationally long-in-the-tooth does not mitigate the disordering effects of capitalist expansion, however. On the contrary, being construed as archaic civilizational formations surpassed by Western capitalist modernity is another sense of primitive and tends to exacerbate the disordering effects with an aura of civilizational degradation and loss of authenticity. Terminologically, primitive and Negro share the same semantic space to the point of synonymy. Those populations designated Negro, however, are seemingly always primitive, this attributed state playing a role, almost as a neo-Aristotelian afterthought, in legitimating their designation: the absurdly Hegelian argument that the primitive, enslaved and made Negro, enters into civilization and thus benefits from the transformation.”

Through this expansive framework, we see that Blackness is not merely a matter of racial categorization but a condition produced by, and resistant to, the violent impositions of Western capitalist modernity’s project of “civilization.” It forms solidarities across homological, analogical, and ecological lines, countering the reductionist logics that have long fragmented human relationality and planetary life under colonial terms of order.

Yet, in expanding the definition of Blackness here, it is important to note that Black politics does exclude some. Those who lack or repudiate a Black ancestry that would form homological kinship and simultaneously disavow the parallel and co-evolving resistance to racial capitalism that defines both analogical and ecological kinships cannot be subsumed under Blackness. This boundary is crucial to preserving the integrity of Black political formations and their historically specific modes of resistance and survival.

That being said, it is possible for those excluded from Blackness to “become-Black” through suffering racial capitalist oppression and either being compelled to adopt parallel forms of resistance or, alternatively, endeavoring to co-evolve their resistance to racial capitalism alongside Black people

This process of becoming-Black, particularly through ecological kinship, can be likened to the symbiotic relationship between the orchid and its pollinating wasp. Just as the wasp enables the orchid’s survival by spreading its pollen, those who engage in solidarity with Black struggles contribute to the flourishing of Black resistance. This mutual adaptation, grounded in reciprocal nourishment and trust, allows diverse communities to thrive in interdependence, nurturing a world where resistance, like a resilient ecosystem, is continuously regenerated through acts of shared care and struggle.

It is important to contrast becoming Black by way of ecological kinship with becoming Black through analogical kinship, because the latter is fraught with limitations. As Afro-pessimism teaches, Black suffering is singular in its abjection, such that no form of oppression experienced by others is truly analogous to the gratuitous violence inflicted on Black people. As Frank Wilderson III explains, the ritualized display of Black suffering serves as a perverse form of healing for (post-)modern global racial capitalist civil society, stabilizing its anxieties through the spectacle of violence:

“Civil society does not want Black land as it wants Indian land, that it might distinguish the Nation from Turtle Island; it does not want Black consent, as it wants working-class consent, that it might distinguish a capitalist economic system from a socialist one, that it might extract surplus value and turn that value into profit. What civil society needs from Black people is far more essential, far more fundamental than land and profits. What civil society needs from Black people is confirmation of Human existence.”

[...]

“Blacks are not going to be genocided like Native Americans. We are being genocided, but genocided and regenerated, because the spectacle of Black death is essential to the mental health of the world—we can’t be wiped out completely, because our deaths must be repeated, visually. The bodily mutilation of Blackness is necessary, so it must be repeated.”

Wilderson emphasizes that such violence functions as a ritual that stabilizes the anxieties of non-Black people, offering a grotesque form of reassurance:

“What we are witnessing on YouTube, Instagram, and the nightly news as murders are rituals of healing for civil society. Rituals that stabilize and ease the anxiety that other people feel in their daily lives. I know I am a Human because I am not Black. I know I am not Black because when and if I experience the kind of violence Blacks experience, there is a reason, some contingent transgression.”

The singularity of Blackness lies in the fact that Black people are reproduced to be enslaved, tortured, and murdered—by commission and omission—without reason and distinction, a condition that affirms the sense and distinctiveness of the humanity of those who are not Black. Others die for a reason, be it a good reason or a bad one; Black people die so that others might recognize the distinction between dying for a reason and dying for no reason at all. Others fear being brutalized, imprisoned, or murdered for one reason or another, good or bad; Black people fear being brutalized, imprisoned, or murdered for no reason at all. Others fear that care and support may be denied to them for justifiable or unjustifiable reasons; Black people fear that there is no reason, justifiable or unjustifiable, for others to care or support them at all.

The popular myth that African people were enslaved purely or primarily for free labor collapses under the weight of the gratuitous violence inflicted on the enslaved. As Karl Marx described, Africa was converted into “a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins,” but the tortures inflicted upon these black-skins reveal that this was not merely a matter of labor exploitation—it was a spectacle of senseless, inhumane brutality that stood in stark contrast to the non-Black, non-slave’s sense of human distinction. In Lose Your Mother, Saidiya Hartman obliterates this myth by recounting only a few of the tortures endured by enslaved Africans across the globe—acts perpetrated at the very same time that the humanism born of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment was consolidating itself.

“In the Gold Coast, his ears were cut off and then he was put to death. In São Tomé, he was drowned in the sea. In Dahomey, he was decapitated. In Kongo, he was asphyxiated in a barracoon. In Santo Domingo, boiling sugarcane was poured on his head and withered the flesh on his body. In Barbados, he was flogged with a seven-headed whip. In Cuba, he was filled with gunpowder and blown up with a match. In St. John, he was burned at the stake, sawed in half, and impaled. In Maryland, he was hanged and decapitated. In Georgia, he was covered with sugar and buried in an anthill. In Curaçao, his face was scorched and his head cut off and placed on a pole for the amusement of vultures. In Surinam, they cut off his hands and crushed his head with a sledgehammer. In Trinidad, he was dismembered and his body parts were thrown into the Atlantic. In Brazil, his ears were chopped off and a dagger buried in his back, his putrefied head displayed in the central square. In Panama, a sword disemboweled him. In Lima, he was paraded through the streets, beaten with the lash, and his wounds were washed with urine and rum. In Jamaica, he was force-fed excrement and burned on a pyre. In Grenada, he was shoved into a kiln and roasted. In Paramaribo, they cut his Achilles tendon and amputated his right leg. In Virginia, he was skinned. In Texas, his feet were bound and he was dragged through the streets by a horse. In New York, he was beaten with cudgels and hanged from a lamppost. In North Carolina, they burned him with torches and threw his body into quicklime. In Mississippi, he was cut to pieces on a wheel of blades. In Washington, D.C., he was mounted like a beast of burden and driven to death. In Alabama, he was tied to a cross, scourged by flaming torches, and beaten with chains. In Louisiana, his belly was sliced open and his entrails spilled out.”

The reality of the Black condition is so horrific that it overwhelms the psyche, leading many Black people to disavow it and embrace myths. Hoping to escape the condition of being “just another mass of Black flesh,” some construct spurious reasons to explain the inexplicable: they invent and then refute justifications for what was never meant to be justified. Those who succeed most convincingly in this endeavor—who persuade the world that their lives and deaths have “meaning”—become Black persons of distinction, “special cases,” granted the “privilege” of having a reason either to live life to term or to suffer premature death, becoming exceptions within the broader framework of gratuitous violence.

The general suffering of other groups under racial capitalism may resemble that of Black people in manner but not in meaning. Indeed, the fact that their suffering typically holds meaning—serves a purpose or explanation within the system—sets a clear limit to the analogy. Only in special cases is the brutalization, imprisonment, or murder of non-Black people under racial capitalism transformed into a gratuitous and meaningless spectacle. Black suffering, by contrast, is typically gratuitous, devoid of inherent meaning—except in such “special cases.” It is only through these exceptional figures that analogies between Black and non-Black suffering find their strongest, though still limited, basis.

For this reason, the planetary extension of Blackness ecologically is the only viable extension. Analogical extensions of Blackness may hold some value, but only insofar as they create the conditions for genuine ecological kinship—where solidarity becomes a shared process of mutual survival and regeneration, rooted in a recognition of interdependence rather than the illusion of equivalence. A Black planet, in this sense, represents a planetary resistance to projects of “civilization” arising from Western capitalist modernity—a resistance defined by the ecological extension of Blackness across the Earth. This planetary resistance does not erase or subsume the singularity of Black suffering; instead, it honors that singularity as the foundational condition that both anchors and informs all solidarities. Resistance to Empire, therefore, does not require the flattening of differences but the cultivation of a web of co-evolutionary struggles, where the recognition of gratuitous violence and shared care coalesce into a regenerative force. In this vision, a Black planet is not only a refusal of racial capitalism’s terms of order but a horizon of collective liberation where human and more-than-human life can thrive.

“Peoples who have been to the abyss do not brag of being chosen. They do not believe they are giving birth to any modern force. They live Relation and clear the way for it, to the extent that the oblivion of the abyss comes to them and that, consequently, their memory intensifies.

For though this experience made you, original victim floating toward the sea’s abysses, an exception, it became something shared and made us, the descendants, one people among others. Peoples do not live on exception. Relation is not made up of things that are foreign but of shared knowledge. This experience of the abyss can now be said to be the best element of exchange.”