Session 8: “At Home in the Surround”

Thanks, as always, to everyone who made it to the last session of the AGAPE Seminar & Studio and to the many present-absences who shaped the session’s proceedings.

Upcoming Session Date: 31 March 2024

Start Time : 10:30 LA / 13:30 NYC / 14:30 São Paulo / 18:30 London / 19:30 Berlin / 20:30 Dar es Salaam / 23:00 Delhi

End Time: 12:30 LA / 15:30 NYC / 16:30 São Paulo / 20:30 London / 21:30 Berlin / 22:30 Dar es Salaam / 01:00 Delhi

Background Readings for the Next Session:

"Give Your House Away, Constantly" - Fred Moten and Stefano Harney Revisit The Undercommons In A Time of Pandemic And Rebellion (Courtesy of Owen)

“Politics Surrounded” by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney

"Without Capture: From Extinction to Abolition" from The Surrounds: Urban Life within and beyond Capture by AbdouMaliq Simone

“Chapter 4: Types of Squatting” from Squatters in the Capitalist City by Miguel A. Martínez (Courtesy of Aramo)

“Reversing the New Global Monasticism” by Emanuele Coccia (Courtesy of Xin Wei)

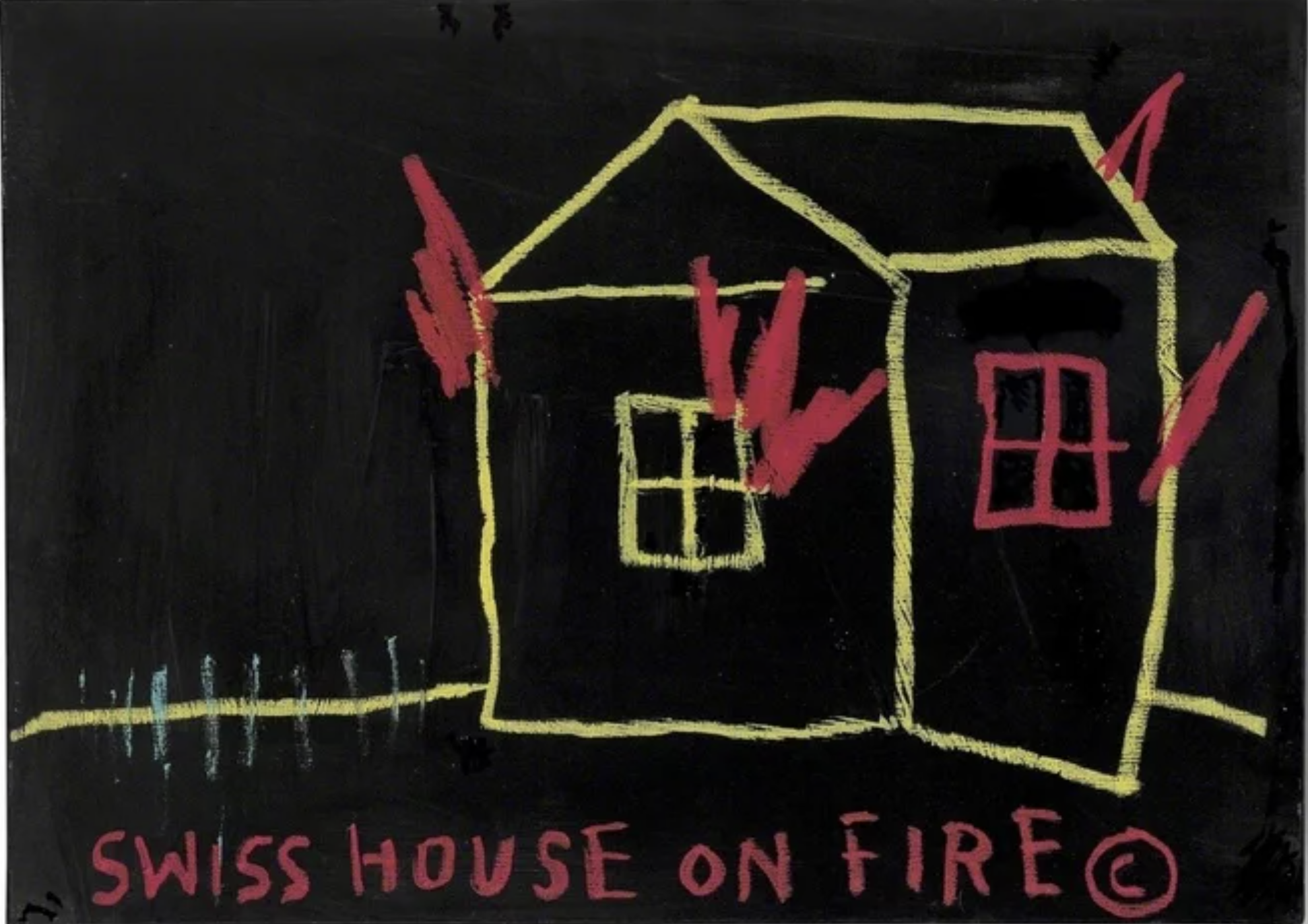

Jean Michel Basquiat, Swiss House on Fire

We began with a recap of the first six sessions of the AGAPE seminar and studio.

In the first session, we marked the distinction between (i) an ideology, (ii) a process, (iii) the product of a process, and (iv) the wake of a process. What was crucial in marking this distinction was noticing how the ideology that characterizes and qualifies the process of colonization (i.e., colonialism as ideology) may be disavowed and the products of a process (i.e., the colony as juridico-legal entity) dispensed with , while, at the same time, the process itself is perpetuated and people are able to take pleasure in and profit from what is left behind in the wake of the process (i.e., coloniality as the addictive toxic byproduct of processes of colonization). To understand the workings of Global Apartheid and Planetary Ecocide, one must understand that processes of colonization needn’t necessarily succeed in creating colonies in order to empower and privilege those who initiate them. In fact, if they are devious enough, those who initiate processes of colonization can maintain and advance their powers and privileges without ever bringing processes of colonization to their logical conclusion in the form of a colony. Colonizers may purposefully arrest the development of the processes of colonization that they initiate, and they may sustain themselves on the remnants, residues, reverberations, and arrangements that emerge in the wake. The dictum of colonizers who are so devious is this: why maintain a colony when coloniality might yield the powers and privileges that one covets?

In the second session, we investigated an insight of Bertolt Brecht’s, “We often speak of the violence of a river overflowing but less of the violence of the banks that confine it.” We remarked upon how colonizers and their proxies often speak of the violence of the forces of nature but hardly ever speak about the violence employed by the forces of Empire as they work to confine nature’s wanderings, dispersals, and migrations. For colonizers and their proxies, finding solutions to environmental problems means managing “natural” disasters first, foremost, and above all else. In conceiving of matters in this way, colonizers and their proxies often refuse to recognize that so-called “natural disasters” are, more and more often, events during which the forces of nature violently liberate themselves from the violent confines imposed upon them by the forces of Empire. For many Indigenous peoples, by contrast, the events that colonizers call “natural disasters” are considered to be difficult guests who arrive unexpectedly and whose sudden arrival one must always be prepared to welcome and live with, regardless of their difficulty. Furthermore, for Maroons, or fugitives from colonial slavery, the events that colonizers call “natural disasters” are considered to be events enabling escape and, as such, serve as triggers to put fugitive plans into action.

In our third session, we noted that what happens in the colonies doesn’t stay in the colonies: the human resources that the metropole extracts from the colony are almost inevitably found to be best controlled by the same means in the metropole as they are in the colonies, and the administration of bordering regimes is where racialized policing in the colonies and racialized policing in the metropoles become (con-)fused and can no longer be teased apart. Border imperialism refers to the manner in which imperial powers, like the European Union and the United States, cite migrants transiting via this (post-)colony and having their point of origin in that (post-)colony as an excuse to interfere in the politics and economy of this and that (post-)colony.

In our fourth session, we looked into my concept of “Maroon Infrastructures”. Maroon Infrastructures are assemblages of administrative statements, technical implements, built environments, and dramatic elements that advance the abolition of colonial slavery and unsettle powers that alienate culture from nature, labor from land, and people from place. One famous “Maroon Infrastructure” that we might regard as an exemplary case study is, of course, the Underground Railroad that conveyed fugitives from colonial slavery to places where they would be able to design freedoms for themselves. Rather than imagining utopias , we asked the following question: what Maroon Infrastructures could we build today, under dystopian conditions of duress, to help us realize the planetary abolition of empires, borders, and forms of accumulation by dispossession, denigration, and devastation.

At our fifth session, we took the measure of the degree to which countries in the “Green Zone” of colonial privilege are the driving force behind a Planetary Ecocide whose most abject victims are the peoples of the “Grey Zone” of dispossession, denigration, and devastation. Global Apartheid serves to keep the peoples of the Grey Zone “in their place”, to keep them from entering the Green Zone where so much stolen wealth is to be enjoyed. In a single year, 2015, the Green Zone effectively robbed the Grey Zone of some 12 billion tons of embodied raw materials, 822 million hectares of embodied land, 21 exajoules of embodied energy, and 188 million person-years of embodied labour, totaling $10.8 trillion in Green Zone prices — “enough to end extreme poverty 70 times over.” Looking at a broader span of time, the twenty five year period between 1990-2015, the Green Zone has effectively stolen some $242 trillion (constant 2010 USD) in embodied raw materials, land, energy, and labor from the Grey Zone.

At our sixth session, we remarked upon the fact that the master’s measures will not dismantle the master’s values. Prevailing measures of “economic development”, “quality of life”, and “standard of living” that have been developed by social scientists and economists in the Green Zone are, in truth, measures of a colonial polity’s capacity to satisfy its addictions to excessive powers and privileges and the titillating and tranquilizing pleasures that attend such. We wondered what alternative, convivial measures might we use to counter colonial measures and to measure the effectiveness of antidotes and therapies that would heal the wounds of coloniality. If we think of the making of mathematical measures as being akin to the making of linguistic turns of phrase, and, if we consider how the poetic turn of phrase makes artful use of emptiness and silence, we could say that, in a similar manner, poetic measures make artful use of the immeasurable and the unmeasured. Returning to the topic of marronage, we began to consider what the poetic measures of marronage might be: ways of living and socializing that are compelled to minimize the measured and measurable traces of “impact” and “human habitation” that they leave behind in this world.

Following the recap, we discussed what it meant for us to take on the legacies of the Maroons together, given the diversity of our ancestors, some colonizers and some colonized. What was recognized, above all else, is that what we must take on is not simply the legacy of the Maroons but the legacies of all those to whom the Maroons related without, romanticizing the past. We may not all be the descendants of Maroons or would-be Maroons, but we are the descendants of those who related to practices of marronage and proto-marronage in constructive and destructive ways that indicate to us what unpayable debts we might owe to the Maroons. As AbdouMaliq Simone writes in The Surround:

[Histories of marronage] point to the ongoing conundrum entailed in moving from confinement to freedom. The flight from captivity was not only an attempt to extricate oneself from the plantation system but a means to unsettle its hegemony, to demonstrate the viability of possible outsides. Yet, any unsettling had to be complemented by the exigencies and practicalities of resettling.

At times, the destinations involved could attain a measure of self-sufficiency, settlements outside the scope of retribution or recapture. But many maroon communities could be established only in territories that necessitated being folded, at least partially, into the sovereignty of that plantation system. This could take the form of regulating the mobility of new generations of runaway slaves or indentured workers or of serving as a supplementary force intervening in internecine conflicts among disparate colonial interests. At still other times, marronage took the form of partial incorporation into other groups that existed at the margins of colonial regimes, such as one of the various indigenous groups often occupying seemingly uninhabitable terrain, which also limited the mobility and maneuverability of the maroon. Whatever the disposition, this transition “from” indicates the dilemmas of a fugitivity, where sometimes there were simply no places to run to, to hide at, to begin anew from, or if there were, they were often situated within inhospitable terrain, problematic partial connections to that which was left behind. All necessitated various ways of becoming imperceptible.

Going further and digging deeper into Simone’s ideas, we considered how marronage involves a kind of blending into the surrounds or, rather, a becoming part of the surrounds, or, better still, a decomposing of oneself into the surrounds. Going further still, I suggested to to you all that the measure of success of a practice of marronage is the degree to which it minimizes the measured and measurable traces of (its) existence apart from the surrounds. Or, in other words, marronage "works" when the signs/signals of its existence cannot be distinguished and distinctly determined apart from the so-called noise of its surrounds, be these surrounds Swamp or Slum.

At this point, we paused and gathered some ideas for how we might proceed in conversation together, given how far we have come. Slowly but surely, we found ourselves “(re-)settling” upon the “unsettling” figure of the home as something to investigate further. Those who identify with the forces of Empire are obsessed with home security: securing a home and securing the comforts of home from the surround. Organized against the forces of Empire, those who identify as or with Maroons make themselves at home in the surround. How can we do, make, say, think, and dwell like Maroons and make ourselves at home in the surround? What makes for a home? Is it really home that we are making in the surround or is it a welcome, welcoming, and welcomed homelessness?

To be continued…